English version of the interview here.

Everyone Somehow Connected to Pottery

Hanada:You were surrounded by pottery from birth.

Was your grandfather the first in the family business of pottery?

Norio Nakagawa: It seems to go back even further.

After returning from the war, my grandfather switched to agriculture, specifically tea fields, so the pottery tradition was interrupted for a while.

Later, my father continued the tea fields my grandfather started, ran a clay business, and eventually started something like a kiln studio.

Hanada: Did many of your classmates also come from families involved in pottery?

Norio Nakagawa: Pottery work isn’t just about making things.

For example, some had parents who were accountants at kilns, or relatives who were presidents of ceramics trading companies.

Everyone was somehow involved in pottery in some way.

To me, it wasn’t about being a strict, dedicated artist making pottery; the commercial aspect was more prominent.

The town had that kind of atmosphere.

Arita was nearby, and we often went there during pottery fairs.

Hanada: Did you talk about pottery with your grandfather or father?

Norio Nakagawa: I don’t remember discussing pottery at all; the tea fields left a stronger impression on me.

Hanada: The tea you gave me the other day was so good.

I was surprised.You brewed it so well, too.

Norio Nakagawa: Thank you.

Acquaintance is continuing the tea fields.

In Mashiko

Hanada: What did you do after graduating school?

Norio Nakagawa: I went to Mashiko.

Unlike the division-of-labor system in Hasami, in Mashiko most processes were done from start to finish, so there was a lot I saw for the first time.

Most things locally were thin porcelain, so I got to appreciate the qualities of earthy pottery.

Hanada: Your experience in Mashiko changed your view of pottery?

Norio Nakagawa: Without Mashiko, I probably would have continued my father’s work as it was.

Hanada: Did you also encounter slipware while in Mashiko?

Norio Nakagawa: Yes, I went with a senior colleague from work to a special exhibition at The Japan Folk Crafts Museum.

That senior colleague started making slipware for fun right after returning from work.

It was a bit awkward…(laughs).

Hanada: Awkward?

Norio Nakagawa: Actually, I wanted to do it too…

So when that senior colleague went independent, I thought, “Alright, let’s do it.”

Hanada: (laughs)

Norio Nakagawa: I looked forward to my days off.

My master at work also bought materials and supported me.

I’m still grateful.

The Master

Hanada: A wonderful master.

Norio Nakagawa: He was generous and flexible.

Also, he was very clear about what was good or bad.

From specific details like plate rim thickness to general ways of thinking, he explained a lot.

He often said, “Ordinary people should get into the habit of looking at good things regularly.”

He even drove us to museums in Tokyo on his days off…

The other day, when he retired, he visited Hasami.

“Are you doing well, Norio?” he asked, driving alone from Mashiko.

Hanada: That’s impressive.

Norio Nakagawa: He took detours, but he was somewhat of a lone wolf.

He kept saying, “You need to make sure you look at good things regularly.”

Hanada: He hasn’t changed his words, then.

Norio Nakagawa: I replied, “Yes, that’s important,” just like before (laughs).

You can learn from masterpieces, or train your eyes…

Though only training your eyes isn’t enough (laughs).

Anyway, I think it’s fine to start by imitating old works.

The Unbalance of Slipware

Hanada: What do you find appealing about slipware?

Norio Nakagawa: At first I focused on the patterns, but now I realize I’m drawn to the overall atmosphere slipware creates.

Hanada: What kind of atmosphere is that?

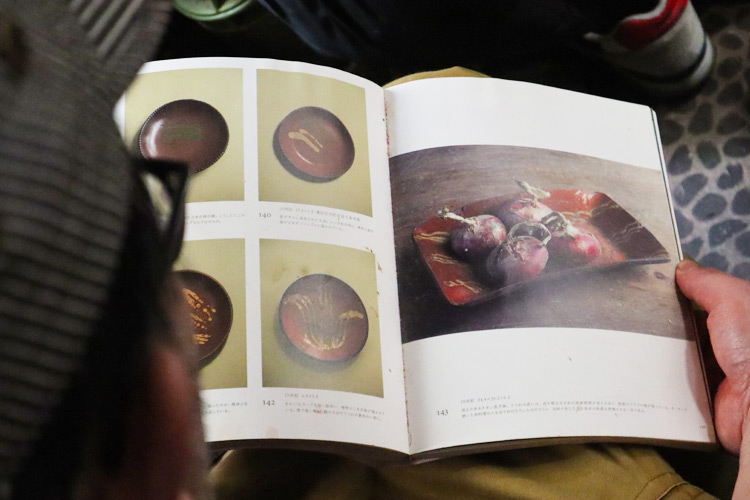

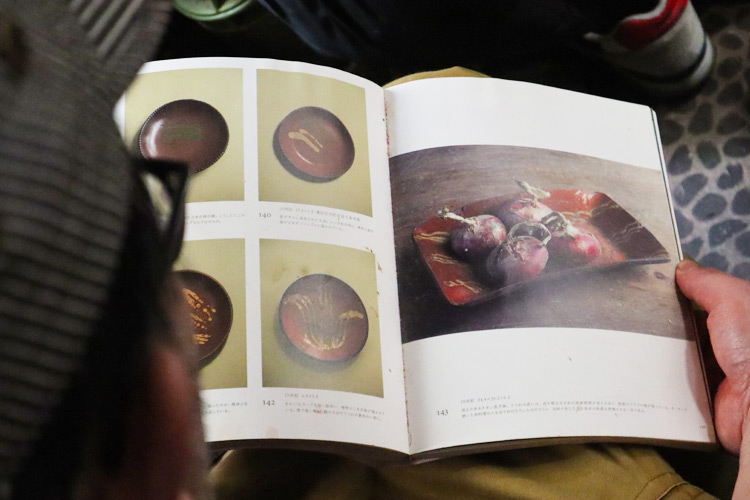

Norio Nakagawa: There’s the charm of well-used antiques, but also the imbalance I notice—like wondering why a line is drawn this way on an otherwise unusual piece.

I like orthodox pieces too, but recently I also like red ones.

That Kind of Feeling

Hanada: What do you value when making tableware?

Norio Nakagawa: Size and shape suitable for everyday use.

Personally, I like simple round or square forms, and I hope people can also accept hexagonal or rimmed pieces.

Regarding size, I first get a feel by using them in daily life rather than starting with exact measurements.

Currently, I favor a plate modeled after an old slipware piece.

Depth, diameter, and the curve (R) are just right.

Depth, diameter, and the curve (R) are just right.

Hanada: Do you mostly use slipware yourself?

Norio Nakagawa: Yes.

I also use pieces made by my father.

Hanada: You also make decorative plates, right?

Norio Nakagawa: Occasionally.

I imagine animals like lions, though they don’t always look very elegant.

Hanada: That kind of feeling, then.

Norio Nakagawa: I like pieces with a relaxed feel.

Intricate or flashy ceremonial pieces don’t come from me.

Of course, I respect them.

Even with masterpieces or antiques, people have likes and dislikes. No one likes everything.

If it’s not to your taste, it’s not to your taste.

Old Kakiemon pieces are amazing, but all I can say is “that’s amazing.”

The Future

Hanada: Is there anything you want to do going forward?

Norio Nakagawa: There’s an old climbing kiln on the top of the mountain our family owns that was used jointly before, so I’d like to make use of it.

Hanada: That sounds exciting.We look forward to your exhibition in April.

Norio Nakagawa:Thank you.I mainly work with slipware, but I’m also planning to show some redware and kiln-transformed pieces, so I’d love for you to see them.

≪END≫

みんな、なんとなく焼き物に関わっている

花田:中川さんは生まれながらにして焼き物に囲まれていました。

家業としての焼き物は、おじいさまが初代ですか。(以下花田-)

中川:もっと前からのようです。

じいさんは戦争から帰ってきたあと農業(お茶畑)に転向したので、一旦途絶えていました。

そのあと、父親はじいさんの始めたお茶畑を引き継ぎつつ、素地屋も営んでいて、そのうち、窯元みたいなことも始めました。

-:学校の同級生にも、たくさん「家が焼き物屋さん」の人がいたのではありませんか。

中川:焼き物の仕事って作るだけではありませんよね。

例えば「親が窯元の経理担当者だ」とか「親戚が陶器の商社の社長だ」とか・・・。

みんな何となく焼き物に関わっている、そんな感じでした。

僕の中では、作家然として、焼き物をかたくなに作っているというよりは、商売としての存在感が大きかったです。

町内がそういうくくりでした。

有田も近所ですし、陶器市の時にはよく遊びに行っていました。

-:おじいさまやお父さまと焼き物の話はされたのですか。

中川:そんな話をした覚えは全くなくて、どちらかというとお茶畑の印象が強いです。

-:この間頂いたお茶、とても美味しかったです。

びっくりしました。

中川さん、淹れるのも上手かったし。

中川:有難うございます。

お茶畑は知り合いが継いでいます。

益子にて

-:学校を卒業後はどうされていたのですか。

中川:益子に行きました。

分業制の波佐見と違って、益子は大体最初から最後まで一貫制作ですから初めて見るものも多かったです。

作っているものも地元では薄手の磁器中心だったので、つちものの良さも知ることが出きました。

-:益子での経験は中川さんの焼き物観を変えたのですね。

中川:益子が無かったら親の仕事をそのまま継いでいたのではないかな・・・。

-:スリップウエアとの出会いも益子にいた頃ですか。

中川:当時の職場の先輩と駒場の民芸館での特別展示を見に行ったのがきっかけです。

その先輩、帰ってきてすぐ、仕事終わった後スリップウエアを作って遊んでいました。

気まずかったですよね・・・(笑)。

-:気まずい?

中川:実は僕もやりたかったから・・・。

で、その先輩が独立された時に「よしやるぞー」って。

-:(笑)

中川:休みの日が来るのが楽しみでした。

勤め先の親方も材料買ってくれて応援してくれました。

今でも感謝しています。

親方

-:いい親方ですね。

中川:寛大で融通の利く親方でした。

それと親方は良し悪しをはっきり言う人でした。

皿の縁の厚みなど、細かい部分での具体的な話から、日ごろの考え方など色々です。

「我々凡人は、日頃からいいものを見る習慣をつけておいたほうがいい」ともよく言われていました。

休みの日に東京の美術館に車で連れて行ってくれたり・・・。

この間も、親方が引退のタイミングで、波佐見に遊びに来たんです。

「紀夫、元気にしてるの?」って。

益子から一人で車運転して・・・。

-:それはすごいですね。

中川:寄り道しながらですけど、まああの人、一匹狼みたいなところ、あったから。

「やっぱりいいもの見るようにしていないとねえ」って言っていました。

-:言うこと変わらないですね。

中川:僕も変わらず「そうですよねえ、そこは大事ですよねえ」なんて答えていましたけど(笑)。

作りを名品に学ぶということもあるし、あと目を鍛えるというか・・・。

まあ、目ばかり鍛えていても仕方ないんですけど(笑)。

いずれにしても、最初は古いモノの模倣でいいと思います。

スリップウエアの持つアンバランス

-:中川さんにとって、スリップウエアの魅力は何ですか。

中川:最初は模様に目が行きがちでしたが、今思えば、スリップウエア全体が醸し出す雰囲気に魅かれているんだと思います。

-:その雰囲気とはどういったものなのですか。

中川:骨董品の使い込まれた良さもありますが、それだけでもなくて「不思議な感じのうつわに、なぜこのような線が入っているのかな」という、僕にとってはアンバランスな部分です。

オーソドックスなものも好きですけど、最近は赤いものも好きです。

ああいうノリ

-:うつわ作りをする上で中川さんが大事にしていることを教えてください。

中川:普段使いに適した「大きさ」と「かたち」です。

個人的には普通の丸や四角が好きで、その上で、六角やリム付きのものも受け入れていってもらえると嬉しいなと。

大きさについては、具体的な寸刻みの寸法をいきなり持たず、まずは普段から使うことで感覚を持とうとしています。

今気に入っているのは古いスリップウエアの大きさを参考にしたこの皿です。

深さといい、径といい、R(立ち上がりのカーブ)といい絶妙です。

深さといい、径といい、R(立ち上がりのカーブ)といい絶妙です。

-:ご自身で使うのは、大体スリップウエアですか?

中川:はい。

それと父が作ったものも使っています。

-:中川さんは絵皿的なものも作られています。

中川:はい、たまには。

獅子などあまり格好よくない動物をイメージしています。

-:ああいうノリですね。

中川:抜け感があるものが好きです。

緻密な絵付けやキラキラな、ハレの日のうつわみたいなものは、自分からは出てこないです。

勿論すごいとは思います。

名品にしても骨董にしても好き嫌いはあるわけで、本当に全部が好きな人って、いないと思います。

趣味じゃないものは趣味じゃない。

古い柿右衛門だってすごいです。

でも「すごいですね」としか言えない。

これからのこと

-:これからやっていきたいことはありますか。

中川:うちの持っている山の上に、昔共同で使っていた登り窯があるので、活用していきたいなと思っています。

-:楽しみですね。

4月の展示会、宜しくお願いします。

中川:宜しくお願いします。

スリップウエア中心で、レッドウエアや窯変のうつわも出したいと思っているので、ぜひ見て頂きたいです。