English version of the interview here.

Kabukicho, Rosanjin, and Wandering…

Hanada: Did you enjoy making things since you were little?

Shingo Arakawa: I loved drawing. In school, I only excelled in art classes. I was terrible at everything else… Also, since my parents were working, I spent a lot of time alone drawing manga or doing craft projects. I felt fulfilled just by creating, and I enjoyed discovering things while making them. Even now, that hasn’t changed. More often than not, I feel disappointed when I open the kiln, but occasionally a piece comes out looking wonderful.

Hanada: When did you first encounter pottery?

Shingo Arakawa: Around the age of 20, after dropping out of fashion school in Tokyo. I lived in Kabukicho, and that chaotic, energetic city shaped a lifestyle that was far from ordinary (laughs).

Hanada: So you first started with fashion?

Shingo Arakawa: Yes, but I quickly got bored and quit within a year. I had no money but plenty of time, so I often browsed books at the nearby Kinokuniya bookstore. That’s where I discovered Masaki Hirano’s book on Rosanjin. Later, I visited the Seikoyo kiln site in Kamakura and some exhibitions, learning about his life and philosophy. I felt a strong sense of structure and rhythm in his work. Perhaps being in such a chaotic city made me notice it. I didn’t really know much about ceramics, but I was struck by how “amazing” it was.

Hanada: What did you do after that?

Shingo Arakawa: I traveled from Asia to Europe for a year, mostly by hitchhiking.

Hanada: Any countries that left a strong impression?

Shingo Arakawa: India, Pakistan, and Iran.

Hanada: You must have met many people along the way.

Shingo Arakawa: Yes, countless people. I was helped many times and am endlessly grateful. Whenever I was in trouble, someone would appear to help.

Meeting a Mentor

Hanada: And then you returned to Japan from your travels abroad.

Shingo Arakawa: I worked for about a year in Minamimakimura Village, at the foot of Yatsugatake, living on-site while learning the local life.

Hanada: You went to many different places (laughs).

Shingo Arakawa: There, I met a potter who introduced me to various aspects of the craft, and I began thinking about apprenticing under someone. Two years later, I discovered the work of Ryuichi Kakurezaki. At first, I thought apprenticing under him would be impossible, but his work was special to me. I went to him with nothing to lose and asked to become his apprentice. He said, “Wait six months,” so I worked nearby in Hiroshima while waiting, thinking he might be testing my resolve.

Hanada: Six months later, you officially became his apprentice.

Shingo Arakawa: Yes, he called me to come for an interview. He asked me to write an essay about my thoughts. Looking back, it was embarrassingly personal writing. Later, I learned the other apprentices weren’t asked to write anything.

Hanada: (laughs)

The Habit of Thinking

Shingo Arakawa: Master Kakurezaki didn’t care at all about my prior experience in pottery. In fact, he said it was better not to have clumsy experience, and even though I knew nothing, he let me help with production from the very first day. He would even ask me, “Do you have any better ideas?”

Hanada: That must have been surprising. Like, “Am I really supposed to answer this?”

Shingo Arakawa: Being asked like that all the time really trains you to think for yourself. And it wasn’t just asking for the sake of asking — he would actually try out what I suggested. He constantly updated his own production methods, so he didn’t care whether it came from a disciple or anyone else. I thought that was amazing.

Hanada: Such things can only be done if one has properly built oneself up, right?

Shingo Arakawa: Master Kakurezaki always kept his workspace impeccably clean, and you could sense a certain dignity in his work and as a person.

In that sense, he scolded me often, because I was the exact opposite.

For example, early on, when I said “Yum…!” while eating with a customer, he said, “That’s not polite, Arakawa!” (laughs)

Hanada: Perhaps he corrected you out of affection?

Shingo Arakawa: No, I think he was genuinely annoyed (laughs).

Hanada: How long did you stay with Master Kakurezaki?

Shingo Arakawa: Eight years. Sometimes, the pieces we made would be repeated three years later, so we had to remember what we did. My role as an apprentice was to prepare everything for him so he could start working smoothly the next morning.

Hanada: That sounds demanding.

Daily Life Lessons

Hanada: You must have learned a lot during your apprenticeship.

Shingo Arakawa: I don’t remember him giving explicit lessons. Most of what I learned came from daily life and conversation. Apprenticing lets you experience how someone with a different perspective approaches work. Even now, I think, “This is what he would say” or “This is what he would do.”

Hanada: So it teaches you to see from different perspectives.

Shingo Arakawa: Yes. He would look at things from a macro view, a micro view, and intuitively. I wanted to learn his flexibility and approach to creating, more than copying his style.

Hanada: It’s an inner quality then.

Shingo Arakawa: Making pottery is not only about “shaping” — it’s also about “becoming,” “emerging,” and “encountering.” That’s what I aim for in my own pottery work.

Independence

Hanada: And then, it was time to become independent.

Shingo Arakawa: Toward the end, Master Kakurezaki told me, “You should start thinking about it,” and I felt, “Yes, it’s about time.” I was also cheeky, asking him for various favors. I even got him to fire the kiln just for testing my own glazes.

Hanada: You really asked for that (laughs).

Shingo Arakawa: Sometimes I suddenly made huge objects and said, “Please fire this,” and Master Kakurezaki couldn’t refuse. He would just say, “If it turns out well, I’ll fire it,” and in the end, he always accepted my requests.

Hanada: He probably thought, watching all that, that it was about time you went independent.

Shingo Arakawa: I think he also considered my age. He would say, “How many more times can you fire the kiln in your life?” He always encouraged thinking on a long-term timeline.

Hanada: And then, independence.

Shingo Arakawa: I originally planned to return to my hometown in Miyazaki. Local Japanese pottery is always fascinating. I wanted to try making work deeply connected to the land. This particular kohiki clay uses nearby soil, but the iron content makes it unsuitable for pottery — it would collapse if fired as-is. By applying a slip coating, we can insulate it and prevent collapse. Kohiki may have been admired for its “ideal white,” but I also see it as a technique to make any soil workable for pottery, based on my own experience.

Hanada: It’s good that you found the right location.

Shingo Arakawa: But it wasn’t easy. I searched for six months, and just when I was about to give up, a property came along. Initially, the house was in terrible condition, but fortunately, it was built with good materials typical of an old folk house.

Hanada: And then began the long days of renovating your studio with your father.

Shingo Arakawa: Yes, and we argued every day. (laughs).

Hanada: What were you arguing about every day?

Shingo Arakawa: Our senses are different, and our ways of thinking are different, so we inevitably clash.

Hanada: Do you remember any particularly memorable arguments?

Shingo Arakawa: Too many to remember(laughs). For example, I wanted attention on fine details, but he would say, “Nobody will notice, so it’s fine as is.”

Hanada: But you were the one being helped, right (laughs)?

Shingo Arakawa: Yes, but still (laughs). My father would leave angrily, then call later saying, “Want to help a bit?” (laughs)

Hanada: He’s a wonderful father.

Step by Step Adjustments

Hanada: It took a lot of effort to finish, I imagine.

Shingo Arakawa: Yes, it took 2–3 years to complete both the studio and living space. I was making pottery at the same time, but most of the work was carpentry.

Hanada: Has your style changed since then?

Shingo Arakawa: No, not really. I haven’t been independent for that long. I visited Hanada just a year ago.

Hanada: So it was still early days.

Shingo Arakawa: Yes, it was my first time selling my own pottery. Before that, I had never sold my work to anyone.

Hanada: I felt a strong presence coming from the pieces, not just skill.

Shingo Arakawa: You saw my early, embarrassing pieces. You really don’t know until you make them. Then, you just refine them step by step.

Listening Carefully

Hanada: What do you value when creating pottery?

Shingo Arakawa: In the beginning, I focused on the clay’s character, but now I keep it simple: if it feels right when it comes out of the kiln, that’s enough.

Hanada: Did Bizen influence your attention to the clay?

Shingo Arakawa: I’ve always loved nature and mountains, so perhaps I subconsciously seek to feel it. I like glazes that feel like water or earth. I want to listen to the reactions of my body and draw out the material’s best qualities. This is different from beauty; even old, seemingly imperfect antique Japanese pottery can feel sublime. That’s the feeling I aim for. My work emerges from interaction with the clay rather than just my inner thoughts. And once fired, I can see the overall result, including any technical or mental imperfections.

Rice Bowls

Hanada: Which pieces give you the strongest sense of achievement?

Shingo Arakawa: Rice bowls.

Hanada: You mainly make rice bowls, right?

Shingo Arakawa: Yes, but it’s hard to explain why. Ever since becoming independent, I’ve mostly thrown rice bowls.

Hanada: Are there rice bowls that remain especially memorable?

Shingo Arakawa: Yes, though even ones I liked at first change over time.

Hanada: So you are always exploring something new.

Shingo Arakawa: I’ve always loved music, searching for new sounds with great effort. I tend to explore novelty. So, rather than making something everyone will like, I focus on what feels right to me at the moment, hoping it resonates with someone else.

Accumulation of Reading

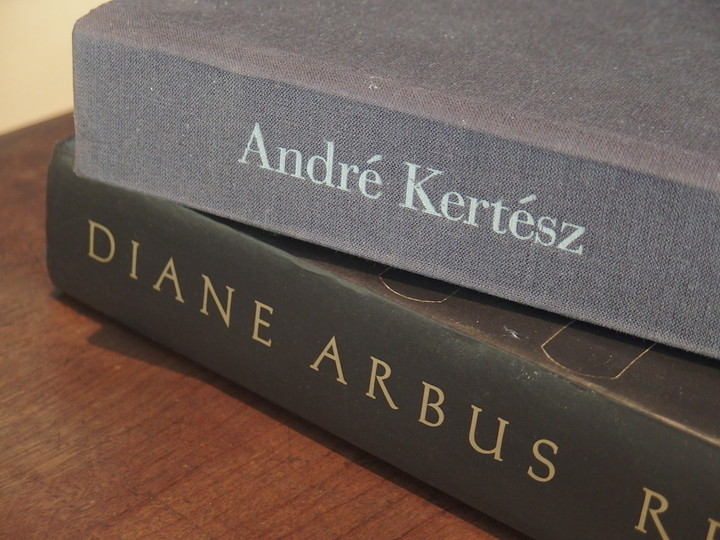

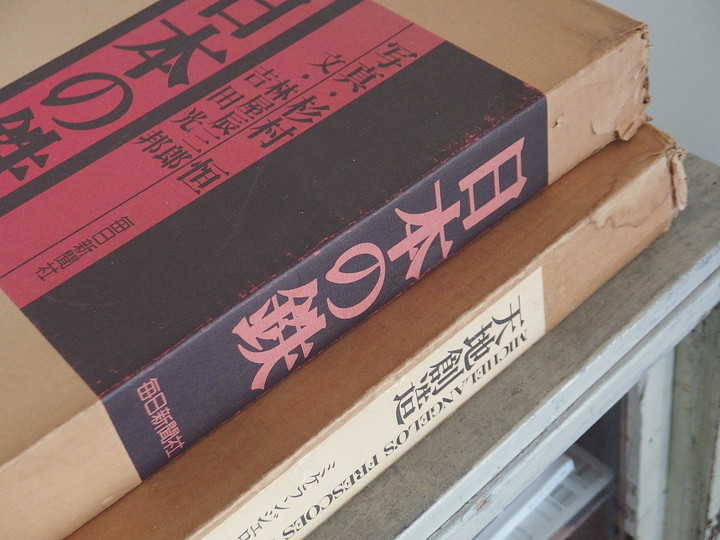

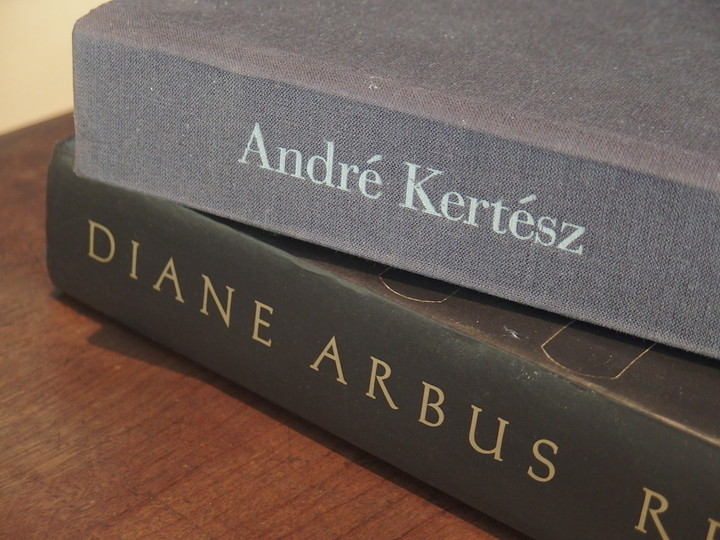

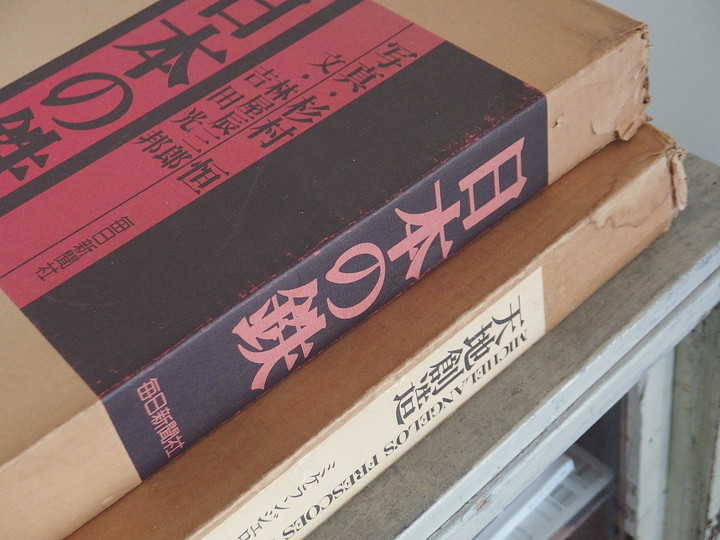

Hanada: Your bookshelf shows a wide range of genres.

Shingo Arakawa: This shelf mostly holds photography and painting books. It’s messy. My reading is mostly detours — books other than pottery or ceramics.

Hanada: Humanities… like folklore or anthropology?

Shingo Arakawa: Comparative culture, history of imagery, contemporary thought… anything.

Hanada: So all these influences eventually connect in your work?

Shingo Arakawa: I don’t try to connect them directly, but while working, I often recall things I’ve seen in museums or mix ideas with miscellaneous objects in my mind. I don’t study pottery photos or books directly; I enjoy trial and error with glazes from scratch, ignoring prior knowledge and experimenting freely.

Hanada: So even struggling, you value progressing by your own efforts.

Shingo Arakawa: Exactly, though it takes a lot of time (laughs).

Hanada: Finally, any words for the upcoming exhibition?

Shingo Arakawa: I want to enjoy it while pushing myself. Hopefully, I can enjoy good sake in Golden Gai (laughs).

Hanada: Thank you very much.

≪END≫

歌舞伎町、魯山人、放浪・・・

花田: ものを作ることは、小さい頃から好きだったのですか。(以下 花田-)

荒川: 絵が好きでした。

学校では図工だけ。

他の教科は全くダメでして・・・。

あと、小さい頃は両親が働いていたので、一人で漫画描いたり工作したりしてました。

作ることそのものに充足感を持っていたし作りながら発見する喜びも感じていました。

今もそれは変わりありません。

窯開けた瞬間にがっくりすることのほうがまだ多いのですが、たまに良い顔をしたものが出てくる・・・。

-: どこのタイミングで焼き物に出会ったのですか。

荒川: 服飾の学校に通うため上京し、中退したあと二十歳くらいの頃。

歌舞伎町に住んでいたのですが、あの混沌としていて、エネルギーをいくらでも受けてくれる街のせいで、まともじゃない生活が日常化してきた頃です(笑)。

-: 最初はファッションだったのですね。

荒川: すぐ飽きて、1年で辞めました。

で、お金はないけど時間はいくらでもあったので近くの紀伊国屋書店でよく立ち読みをしていたんです。

そこで平野雅章さんの魯山人の本に出会いました。

そのあと、鎌倉の星岡窯跡や展覧会に行って、彼の生き方や物語を知ることになり、興味を持つようになりました。

彼の中に太い軸、律のようなものを感じたんです。

混沌の街中にいるからこそ気付けたのかもしれません。

元々陶芸に関心があったわけでもないし、よく分からなかったのですが「すごい」って強烈に感じたのを覚えています。

-: その後はどうされていたのですか?

荒川: アジアからヨーロッパまで、ヒッチハイクで1年間放浪しました。

-: 印象に残っている国はありますか。

荒川: インドとパキスタンとイランですね。

-: 色々な人々との出会いもあったのではないですか?

荒川: はい、数え切れないほど・・・。

ずいぶん助けられました。

感謝してもしきれません。

困っていると必ず助けてくれる人が現れるんです。

恩師との出会い

-: そして海外の放浪から帰ってきます。

荒川: 日本に戻ってきて、1年くらい八ヶ岳の麓の南牧村で、住み込みで働いていました。

-: 色々、行きますね(笑)。

荒川: そこで、出会った陶芸家に話しを聞き、どこかに陶芸で弟子入りすることを考え始めました。

その2年後くらいに隠崎隆一先生の仕事に出会います。

最初は、隠崎先生への弟子入りは無理だと思っていましたが、やはり隠崎先生のお仕事は僕にとっては特別だったので、諦めきれずダメもとで先生のところへ行って、弟子入りをお願いしました。

そうしたら「半年待って」と言われたので「覚悟を試されているのかな」なんて思いながら、近くの広島で働きながら待っていました。

-: 半年後、晴れて、弟子入りが叶う。

荒川: 面接に来るように電話が掛かってきました。

思いを作文にして持ってくるように言われて・・・。

今考えると、めちゃくちゃ恥ずかしいことを書いていました。

しかもあとで知るのですが他の弟子は書かされていなかった・・・。

-: (笑)

考える癖

荒川: 隠崎先生は、僕の焼き物の経験については、何も気にされていませんでした。

むしろ「ヘタに経験なんて無いほうがいい」と言われ、何も知らない僕に初日から制作を手伝わせてもらえたうえに、「何かいい方法ないか?」なんて聞いてもらえる。

-: びっくりしますよね。 「俺、答えちゃっていいの?」みたいな。

荒川: いつも聞かれていると、考える癖がついてくるんですよ。

しかも、ただ聞いてくるだけでなくて、本当に答えたことを試してくれる。

元々、制作方法をどんどん更新していく方だったので、弟子だろうがなんだろうが頓着しない。

すごいな、と思いました。

-: 自分をしっかり作り上げていないと出来ないですよね、そういうことは。

荒川: 先生、いつも仕事場をピシッときれいにしていたし、作品にも、人としても品格のようなものが感じられます。

そういう意味ではよく叱られました、僕は真逆ですから。

始めの頃、お客さんと食事をしているときに「うめー!」と言ったら「『うめー』じゃないだろう、荒川君」って(笑)。

-: 可愛いからこそ、言ってくれたのではないですか。

荒川: いや、本当に頭にきていたのだと思います(笑)。

-: 隠崎さんのところには、どれ位いたのですか?

荒川: 8年です。

先生の作品は、同じものを作るのが3年後だったりするので、忘れた頃にやってくる感じでした。

だから、やっていて面白い。

とはいえ、その3年前を覚えておくのが弟子の仕事です。

前日に「明日○○作るから」って言われたら、それ用の道具を準備して、先生が朝気持ちよく仕事を始められるようにしておく。

-: なかなか大変ですね。

普段の暮らしから

-: 修行時代は色々と勉強になったことも多かったと思います。

荒川: 具体的に教訓めいたことを言われた覚えはほとんどありませんが、普段の暮らしや会話から多くを学ばせていただきました。

あと、弟子入りすると、自分と違った物差しを持っている人の仕事に突っ込んでいって体で感じることが出来る。

「先生ならこう言うだろうな」とか「ああするだろうな」とか、今でも頭をよぎることがあります。

-: 別の目線を持てると言うことなのですね。

荒川: 先生は俯瞰したり、微視的に見たり、直感的に見たり、色々なことをする方で、それを学んでいくことができました。

先生のスタイルを直接に受け継ぐと言うよりは、先生がものを生み出す姿勢や自在さを学びたいなと思っていました。

-: 内面の部分ですね。

荒川: かたちは「作る」という側面もありますが、「なる」「生まれる」「出会う」ものだと感じますし、そういうことを目指したいなと思っています。

独立

-: そして、そろそろ独立に。

荒川: 終盤になると先生も「そろそろ考えておきなさいよ」と言われて、僕も「そろそろだな」と思い始めていました。

僕も僕で、生意気に先生に色々なことをお願いしていました。

自分の釉薬のテストのためだけに窯焚かせてもらったり・・・。

-: よく、そんなこと頼みましたね(笑)。

荒川: 突然馬鹿でかいオブジェ作りだして「これ焼かせてください」なんて言ってきたら、先生も断れないじゃないですか。

先生も「出来がよければ焼くわ」とか言っていて・・・。

結局断られず、受け入れてくださるばかりでした。

-: そういうことを見ながら先生も「そろそろかな」と思っていたのでしょうね。

荒川: あと、僕の年齢も考えてくれていたと思います。

「人生で何回窯が焚けるだろうか」と。

常に長い時間軸でモノを考えたり、提示してくれたりしていました。

-: で、独立ですね。

荒川: 元々、地元(宮崎)に帰るつもりでした。

土地に根ざした焼き物は、どこのものにしても魅力的です。

「そういうものをやってみたいな」とずっと思っていました。

この粉引きはすぐそこの土を使っているのですが、鉄は吹くし、本当に焼き物に適していない。

そのまま焼いても、ぺちゃんこに焼きつぶれちゃうんです。

ところが化粧で皮膜することで遮熱すると、つぶれなくなる。

粉引きというのは「憧れの白」でもあっただろうけど、どんな土でも焼き物として成立させる技法としてもあったのかもしれないと、自分の経験から思いました。

-: 良い場所が見つかってよかったですね。

荒川: なかなか見つかりませんでした。

半年間、物件を探し続けていて、諦めかけたころに話が舞い込んできました。

最初、家の状態は、実にひどかった・・・。

ただ、古民家らしい良い素材で建ててあったので、幸いでした。

-: そして、お父様とのリフォームの日々が始まる。

荒川: はい、毎日、ケンカしながら(笑)。

-: なんでケンカ?

荒川: まず感覚が違う。

そして、思考のスタイルも違うので、絶対ぶつかりますよね。

-: 印象深いケンカは?

荒川: そんなこと、分からないくらいケンカしています(笑)。

例えば、細部の処理なんて、僕にしてみれば一番こだわって欲しいところなのですが「あんまし見えないんだから、ここはいいだろ」とか。

-: ただ、荒川さんは手伝ってもらっている立場ですよね(笑)。

荒川: それは、そうなんですけどね(笑)。

親父、怒ってよく帰っていましたよ。

で、しばらくすると「なんか手伝うか」って電話を掛けてきてくれる(笑)。

-: 良いお父様ですね。

コツコツ修正

荒川: 結局、この仕事場と住まいの二軒を仕上げるのに2-3年かかりました。

焼き物も同時進行で作ってはいましたが、その間はほとんどが大工仕事でした。

-: その頃から、作るもののスタイルは変わりませんか。

荒川: いや、変わるも何も、独立してからそんなに経っていませんから。

花田さんに伺ったの、まだ1年前ですよ。

-: まだそんなものでしたかね。

荒川: そうです。

あの頃が初めてですよ。

それまで誰にも、自分の焼き物を売ったことありませんでしたから。

-: モノから発する、強いものを感じました。

上手いとかなんとか、そういうことじゃなくて。

荒川: 松井さんは、僕の最初の恥ずかしいものの頃から見ていますからね。

ほんと、作ってみないと分からないんです。

そして、それをずっと、コツコツ修正していく。

耳を澄ませていたい

-: 荒川さんが焼き物を作るときに大事にしていることはありますか。

荒川: 最初の頃は土味に執着していましたが、今はそうでもありません。

窯から出したときに「いいな」って思えればそれで良いとシンプルに考えるようになりました。

-: 土味にこだわるのは備前にいた影響ですか。

荒川: 僕は元々自然が好きで、山にもよく行きますが、自然を感じたいと無意識のうちに求めているのかもしれません。

この釉調も水を感じるから好きとか、大地を感じるとか。

身体が反応する世界に耳を澄ませていたいです。

うまく素材の良さを引き出せたらなって。

-: 素材を活かすわけですね。

荒川: 美醜とはまた違った部分です。

古くて一見きたないような窯傷のある骨董などでも崇高さを感じるときありますよね。

「ああなれたらいいな」と思います。

自然の静かな魅力に気付けるようになりたいです。

モノは僕の内面から表出すると言うよりは、土とのやり取りの中から呼応して出てくる感じです。

で、そして、焼き終わると、総合的なものを見てとれる、技術や精神状態の未熟さなども含めて。

飯碗ばかり

-: 作っていて手ごたえのあるものは何かありますか。

荒川: 飯碗です。

-: 飯碗ばかり作っていますよね。

荒川: そうなんです。

でも、それを何故かと問われても言葉にすることは難しいです。

いずれにしても独立した頃から飯碗ばかりひいていました。

-: 今でも心に残っている飯碗はありますか。

荒川: ありますが、最初の頃いいなと思っていても、変わってきます。

-: 常にそういう感じなのですね。常に何かを新たに探索している。

荒川: 昔から音楽が好きで、自分にとっての新しい感覚の音を凄い労力使って探していましたから(笑)。

新奇探索傾向が強い。

そんなだから誰にでも受け入れられるものよりは、僕の場合「単純にその時に僕自身がいいなと思えるものを、誰かに響くといいな」ぐらいなほうが自然なんですね。

読書の蓄積

-: 荒川さんの本棚を拝見すると、ジャンルも色々です。

荒川: ここの棚は写真、絵画が中心でしょうか。

ゴチャゴチャです。

読書も寄り道ばかり(笑)。

やきもの、陶芸以外の本がほとんど。

-: 人文系・・・、民俗学とか人類学とか。

荒川: 比較文化や、イメージの歴史、現代思想・・・なんでも。

-: どこかで繋がってくる、ということですね。

荒川: 繋げようとはしていませんが、仕事をしている時、前に美術館で見ていたものが出てくることもあるし、そこらへんの雑器と何かが混ざってポンと頭の中で重なったり編集されて出てくることもあります。

普段から、直接的に焼き物の写真や本を読んで勉強しようという気持ちはあまりありません。

釉薬も一からの試行錯誤を楽しんでます。

何か知識が入ってもあえて無視してとにかく試してみることをします。

-: 四苦八苦しながらでも、自らの力で進んでいくことの活力や喜びを大切にされているのですね。

荒川: そんなところだと思いますが、ただ、時間が掛かって仕方がない(笑)。

-: さて、企画展に向けて一言、お願いします。

荒川: 自分の尻を叩きつつ、楽しみたいと思います。

ゴールデン街でうまい酒が呑めますように(笑)。

-: 有難うございました。