English version of the interview here.

Discovering a Love of Cooking in Elementary School

Hanada: Before you began working with ceramics, you were involved in cooking professionally, weren’t you?

Mutsuhiko Shimura: For about ten years, I think.

My family ran a restaurant, so it felt like a natural path for me to go into cooking.

Hanada: So you watched your father cooking from a young age?

Mutsuhiko Shimura: No, not really. I’d come home from elementary school and cook for myself.

Hanada: Wow, that’s impressive for a grade schooler.

Mutsuhiko Shimura: Well, it was just simple things, like fried rice.

Hanada: Did someone teach you how?

Mutsuhiko Shimura: I learned by watching and copying. I even invited friends over and made oden once.

It didn’t taste very good, so it wasn’t especially popular (laughs).

I didn’t use any recipes—just relied on my instincts, which probably wasn’t a good idea.

Hanada: Still, I imagine your friends enjoyed it.

Mutsuhiko Shimura: Regardless of the taste, I think they had fun.

What I Like, What I Want to Make

Hanada: How did you first encounter ceramics?

Mutsuhiko Shimura: Through my work in cooking, I gradually became interested in ceramics.

I started attending a pottery class as a hobby, and before I knew it, I wanted to pursue it more seriously, so I enrolled in a ceramics school in Seto.

Even then, I still didn’t intend to make ceramics my profession.

After graduating from the ceramic training school, I had the opportunity to study under Mr. Nagae (Sokichi).

That was when I began to think about making a living through ceramics.

Hanada: You must have learned a great deal under Mr. Nagae.

Mutsuhiko Shimura: Rather than “learning,” it was simply fascinating.

We went to places connected with Chinese Jian ware, handled clay, examined ceramic shards and analyzed the glazes… So I was strongly influenced by Chinese ceramics, and at first, those were the works I was most drawn to.

Hanada: From the Northern Song period?

Mutsuhiko Shimura: Yes. At the time, I was attracted to things that felt crisp and taut.

Hanada: Were those the kinds of works you wanted to make?

Mutsuhiko Shimura: Not exactly. I admired them, but I knew I could never make something like that.

Hanada: So more of an aspiration. You also became interested in Joseon and Goryeo ceramics.

Mutsuhiko Shimura: I liked visiting antique shops, and as I saw more pieces, I gradually became drawn to those works.

Hanada: True—you can’t really buy Song pieces yourself, but Joseon ware might be possible.

Mutsuhiko Shimura: Well, you can’t really afford them either. And if you see one at that price, it’s almost certainly a fake (laughs).

Hanada: What is it about Joseon ceramics that appeals to you?

Mutsuhiko Shimura: The texture—the softness. It’s quite difficult to express that quality.

Hanada: Many Japanese people are drawn to Joseon ceramics not only for their forms and designs, but for that atmosphere—something hard to put into words.

You moved from cooking to ceramics. Do you see any common ground between the two?

Mutsuhiko Shimura: I like natural materials, so in that sense they’re similar—raw clay, natural ash, and so on.

Hanada: Why choose natural materials?

Mutsuhiko Shimura: When you use today’s highly processed materials, you can easily make something that looks clean and beautiful.

But after using them for a while, I start to feel that something is missing.

Hanada: Do you get tired of them?

Mutsuhiko Shimura: Yes. They catch your eye at first because they’re beautiful, but…

Hanada: Would you describe your work as a “reproduction” of old ceramics?

Mutsuhiko Shimura: It’s reproduction plus something of my own.

Even so, I’m not aiming to make them look exactly the same.

Hanada: What is it that you want to add?

Mutsuhiko Shimura: That “something of my own” is the hardest part.

Perhaps making things is the process of continually searching for that.

Moments of Joy, Time Well Spent

Hanada: In that process, what are the moments that make you happiest?

Mutsuhiko Shimura: When a piece comes out of the kiln. That moment when you think, “Yes, this is good.”

In my early days, when I was experimenting a lot, I felt that kind of excitement more often.

Recently, I’ve started working on Ido ware.

Hanada: That’s quite a challenging direction.

Mutsuhiko Shimura: I’m in the middle of various experiments right now. I hope they turn out well.

In another direction, I’m also thinking of trying something fun and cute—drawing motifs in a Mishima-style inlay manner.

Hanada: Do you enjoy the meticulous work of inlay?

Mutsuhiko Shimura: …

Hanada: Maybe not so much… (laughs)

Mutsuhiko Shimura: Honestly, I enjoy the time spent thinking about patterns more.

I like combining different classical motifs and ideas.

Admired Ceramics and My Own Work

Hanada: Finally, what ceramics do you admire most?

Mutsuhiko Shimura: For Ido ware, it would be Kizaemon—or perhaps Shibata.

Hanada: Do you prefer Ao-Ido?

Mutsuhiko Shimura: Yes. With Shibata, it’s the rise of the form, the energy of the wheel marks, and that khasan texture. The shape and the surface, I suppose. I’ve never held one, but it gives me chills just thinking about it.

I also love the large white porcelain jars at the Folk Crafts Museum.

Recently, when I visited the National Palace Museum in Taiwan, I saw many pieces of Chinese Ding ware.

There were mountains of them—pieces you’d never see in Japan.

The level of labor involved is on a completely different scale from today.

Hanada: They weren’t the work of individuals alone, after all.

You travel quite a bit, don’t you?

Mutsuhiko Shimura: Since I make Joseon-style ware, I go to Korea, as well as Taiwan, Thailand, Laos…mostly around Asia.

Hanada: And within Japan?

Mutsuhiko Shimura: (after a pause) Hot springs, maybe…

Hanada: (laughs) Sorry.

I was hoping for a slightly more “ceramic-artist-like” answer.

Mutsuhiko Shimura: Ah—I did go to Arita.

Miyaoka (his wife Maiko Miyaoka, who also makes ceramics) wanted to go.

Hanada: Thank you for the suitably ceramic-artist-like answer (laughs).

You’ve made many pieces over the years. Are there any that stand out in your memory?

Mutsuhiko Shimura: There are sake bottles and cups that turned out particularly well and still stay with me. Hakeme, Gyeryongsan…there was also an ash-glazed sake bottle.

I sometimes wonder where they are now, and who is using them.

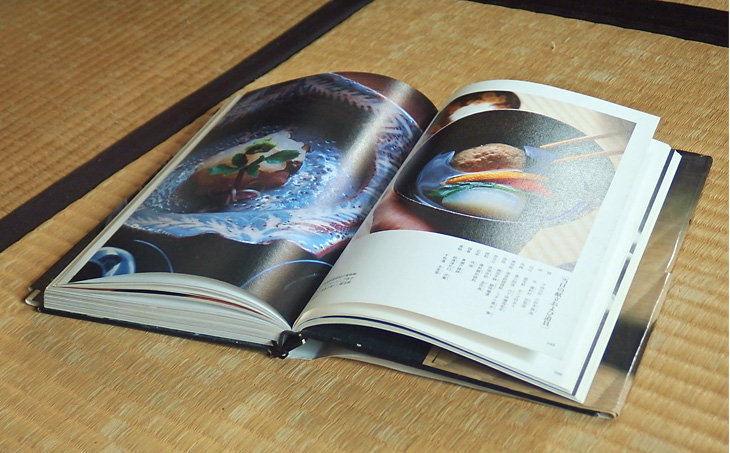

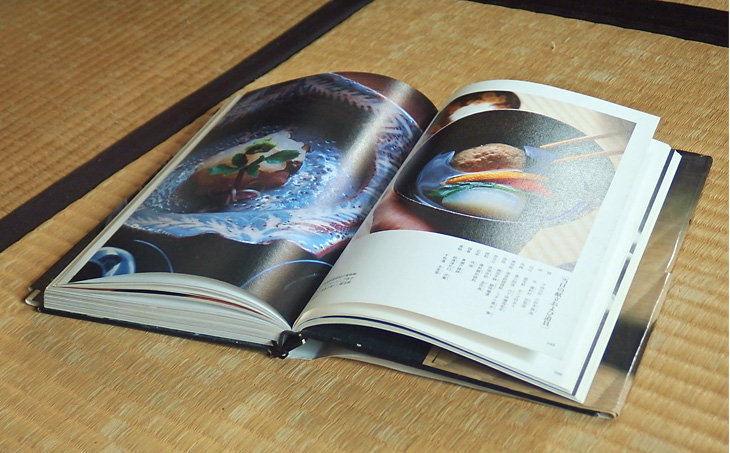

As for celadon, I often make a five-sun molded bowl—it’s a standard piece I’ve made for years.

Hanada: It’s very practical, and also has presence.

Mutsuhiko Shimura: Some people even use it as a matcha bowl, or as a serving bowl. I use it myself quite often—it goes with just about anything.

Celadon for Summer Dishes

Hanada: Finally, could you share a few words for the August exhibition?

Mutsuhiko Shimura: This time, I changed the firing slightly—especially for the Mishima inlay pieces, leaning more toward oxidation.

Compared to before, the surface has a slightly yellowish tone; the patterns come out more clearly, and it’s quite interesting. I’ve also made many works with more distinct motifs this time.

And I think celadon works well with summer dishes. I hope visitors will enjoy these expressions that feel appropriate for August.

料理に目覚めた小学生時代

花田: 志村さんは焼き物の仕事を始める前、料理のお仕事をされていました。(以下 花田-)

志村: 10年間くらいでしょうか。

実家が料理屋だったので、自然な流れで料理の仕事に就きました。

-: 小さい頃からお父上の料理する姿は見ていらっしゃったのですね。

志村: いえ、ほとんど見ていません。小学校から帰ってきて、自分で作る感じ。

-: へえー。すごい小学生ですね。

志村: と言っても、炒飯みたいな簡単なものですよ。

-: 誰かに教えてもらったのですか。

志村: 見よう見まねで。友達呼んで、おでん作ったこともありました。

味はいまいちで、評判はあまり良くなくて(笑)。

レシピを見ず、勘で作ったのがよくなかった・・・

-: 友達、喜んでくれたんじゃないですか。

志村: 味はともかく、面白かったとは思います

好きなもの、作りたいもの

-: うつわ作りとの出会いは何だったのですか。

志村: 料理の仕事の中で、焼き物に興味を持ち始めたんです。

で、趣味で陶芸教室通っていたら、もっと深くやりたくなって瀬戸の学校に通い始めました。

それでもまだ、焼き物を仕事にするつもりなんてなかったんです。

で、窯業学校出たあと、長江(惣吉)さんのところで勉強させてもらえることになったんですね。

その頃からです、焼き物で生きていこうって思い始めたのは。

-: 長江さんのもとでは、色々学べたのではないでしょうか。

志村: 学ぶっていうか、すごく面白かったです。

中国の建窯のほうへ行って、土いじったり、陶片見たり、その釉薬調べたり・・・

それなので、中国の焼き物に影響を受けて、最初はそういったものが好きでした。

-: 北宋の頃のものでしょうか。

志村: そうですね。その頃はなんかシャキっとしたのが好きでした。

-: そういうものを目指したいと?

志村: いや、やりたいのとは違うんですけどね。あんなものは絶対に作れないので。

-: 憧れですね。李朝や高麗のやきものにも興味を持つようになる。

志村: 骨董屋巡りも好きで、色々目にするうちにそういうものにひかれていったんです。

-: 確かにね。宋のものは自分で買えないけど、李朝のものなら買える。

志村: もちろん買えないし、そんなところにあったら、ほぼニセモノじゃないですか(大笑)。

-: 志村さんにとって李朝の焼き物の魅力ってなんなのでしょうか。

志村: 質感、柔らかい感じ。それを表現するのがなかなか難しいのですが。

-: 日本人の多くが李朝の焼き物を好きな理由って、造形とか意匠の部分もあるんでしょうけど、あの雰囲気というか、言葉では言い表せないような、気分のようなものなのでしょうね。

料理から焼き物の道へ。志村さんにとって焼き物と料理に共通点はあるのでしょうか。

志村: 自然の原料が好きなので、そのあたりは似ているのかな。原土だったり、自然灰だったり。

-: 自然のものを使う理由とは?

志村: 現代の加工された優れた材料を使うと、見た目キレイなものがすぐできます。

でも、なんか段々使っている内にそういうことでもなくなってくる気がするんです。

-: 飽きてしまうのですか。

志村: えぇ、キレイで最初はパッと目をひくんですけど・・・

-: 志村さんの仕事は、古陶の「再現」ということになるのでしょうか。

志村: 再現プラス自分の何か、です。

ただ、再現と言っても、見た目をそっくりにすることを目指すっていうわけでもないんですが。

-: 足したいものってなんなのでしょう。

志村: その「自分の何か」っていうのが難しいんです。

モノ作りってそれを追い求める作業なのかもしれませんね。

嬉しい瞬間、楽しい時間

-: そういう中で、志村さんにとって嬉しい瞬間とは?

志村: うれしいのは焼きあがった時。「いいぞ!」っていう瞬間。

試行錯誤していた初期の頃には、そういう感動が多かった気がします。

最近は井戸を始めています。

-: また大変なこと始めましたね。

志村: 実験を色々している最中です。うまくいくとよいのですが。

あと違う方向性で、楽しくて、可愛いモチーフを三島の象嵌っぽく、描いてみようかなと思っています。

-: 象嵌の細かい作業も好きなんですか?

志村: ・・・

-: そうでもない・・・(笑)

志村: 正直言って、文様考えているときのほうが楽しいです。

色々古典の文様などを組み合わせてみたり・・・

憧れの焼き物と自分の仕事

-: さて、志村さんにとって、憧れの焼き物って何でしょう。

志村: 井戸なら喜左衛門、いや柴田かな。

-: 青井戸のほうが好きなんですか?

志村: はい。

柴田は、あの立ち上がりやロクロ目の勢い、そしてあの梅花皮感。

かたちと肌合いですかね。手に取ったことありませんが、ゾクッとします。

民芸館にある白磁の大壺なんかも大好きです。

この間、台湾の故宮に行った時に、中国の定窯のものもたくさん見てきました。

山のようにありましたよ。日本じゃ見たことないようなものまで。

手のかけ方が今とは桁違いですね。

-: 当時は一個人の取り組みではありませんからね。

志村さん、色々なところに旅されますよね。

志村: 李朝作っているんで、韓国にも行きますし、台湾、タイ、ラオス・・・ま、アジアが多いですかね。

-: 国内は?

志村: (しばらく考えて)温泉とか・・・

-: (笑) すみません。

もう少し陶芸家らしいお答えを期待してしまいました。

志村: あ、有田は行きました。

宮岡(麻衣子さん 奥様で同じくうつわ作りをしています)が行きたいって言うんで。

-: 陶芸家らしいお答え、有難うございます(笑)。

ところで、志村さん、これまでたくさんのうつわを作ってこられました。

ご自身が作ったもので、印象に残っているもの、なにかありますか。

志村: 徳利とか猪口とか、うまくいって今でも心に残っているものはあります。

刷毛目、鶏龍山・・・あと灰釉の徳利もありました。

今、どこで誰に使ってもらっているんでしょうね・・・

あと、青磁の陽刻五寸鉢なんかは定番で、昔からよく作っています。

-: あれ、使いやすいし、華もある。

志村: 抹茶茶碗として使ってくれる人もいるし、鉢としても。

自分でもよく使うんです。何でも合います。

夏の料理に青磁

-: さて、8月の展覧会に向けて一言お願いします。

志村: 今回焼き方、少し変えたんです。特に三島の象嵌なんかは、酸化気味にして。

今までと違う、黄色味がかった肌合いというか、文様がハッキリして、面白い感じです。

あと今回文様をはっきりしたものも多く作っています。

あと青磁は夏の料理にも合うと思いますしね。

そういった八月らしい表現をご覧頂く方々に楽しんでもらえたらな、と思います。