English version of the interview here.

Tokuhiro Masubuchi is exhibiting for the first time since last August.

Previously, we had a broad conversation with him.

This time, we focus on the work that symbolizes his current practice: carving.

What does “carving” mean to Mr. Masubuchi?

Starting to Carve

Hanada: What inspired you to start carving?

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: The trigger was the permanent collection at the Tokyo National Museum. There were rows of craftworks—woodwork, metalwork, exquisite maki-e, and so on. I thought, “Ah, I want to try that!”

Hanada: You can really take your time looking there, too.

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: On one hand, I felt “I can’t compete with this,” but on the other hand, I wanted to approach it. So I thought, “Well, I’ll do as much as I can.” My grandfather’s influence might have been strong, too.

Hanada: What kind of influence was that?

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: When I was a student, he specialized in metalworking and engraving, and later in life he did woodwork. The pieces he made were scattered around our house.

From an early age, I felt the comfort of hammer marks and chisel traces.

Hanada: So you ended up pursuing those elements within the realm of ceramics.

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: Yes, ceramics was the only medium I could work with. And then I wondered again whether it was necessary to aim for that within ceramics.

Hanada: Why did you choose ceramics as your medium of expression?

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: Leaving chisel or cut marks on shaped clay and then applying glaze to shape it—I realized that this can only be done in ceramics. For example, cloisonné enamel is difficult to use as tableware, so it wouldn’t work as well.

Hanada: And that’s how you devoted yourself to carving.

Machines and Human Hands

Hanada: I think your carving is quite far from the typical “handmade” image people expect. It doesn’t feel “handmade” in the usual sense.

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: I think so.

Hanada: So there must be a reason to do it by hand. Is there a part that “a machine couldn’t do”?

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: I hope so (laughs). The human hand “goes off” in a good way. It doesn’t always follow the guideline exactly, and in the first place, the guideline wasn’t precisely measured.

But when the hand goes off like that, it covers up its own imperfections

Hanada: Covers up… in other words, it softly corrects itself.

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: I’ve spent 47 years living by making compromises and covering things up. My life has been one of constant improvisation… (laughs)

Hanada: Don’t start joking all of a sudden (laughs).

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: It’s important to maintain a certain touch while aligning where it counts. Machines may be better at aligning points exactly, but for turning multiple points into lines, humans still have the edge, I think.

Never Surpass the Original

Hanada: You put a lot of effort into this work.

Tokuhiro Masubuchi:I’ve considered using molds. But with molds, you can never surpass the original; what you produce is always just a copy of the mold.

Hanada: It would make the edges less sharp and the result more softened?

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: Going from the original to the master mold and then using that mold causes blurring. Then pressing clay into the mold adds another layer of blur.

Hanada: So it’s not that molds are bad, but for your expression, you have no choice but to work directly from the original.

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: Soft-focus mold works are nice, but for me, it’s about the original model.

Hanada: You’ve been working directly from the original model all along, then.

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: Even industrial prototypes are the coolest. Clay car models, for example, are carved directly by craftsmen. Then they derive press lines from that. Adjusting for technology and economics introduces compromises. What I do in carving is always like working with prototypes.

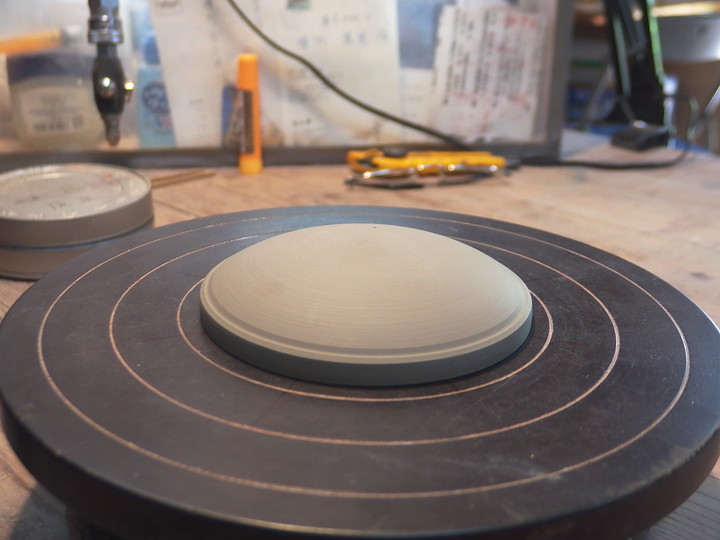

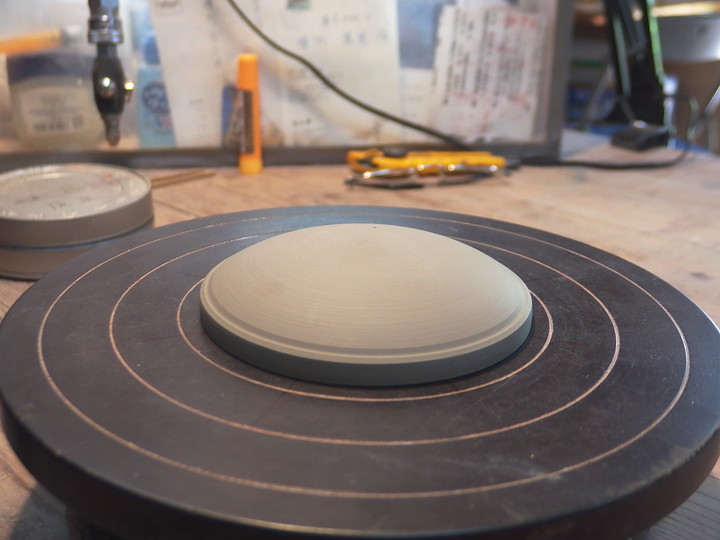

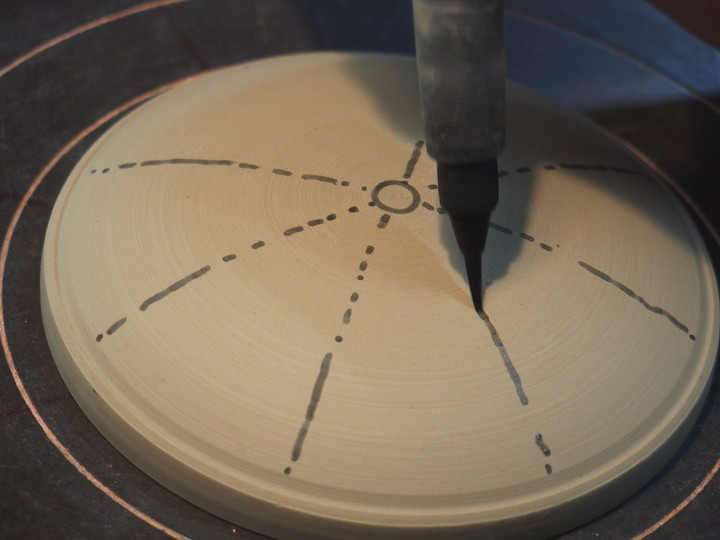

Marking Guidelines

Hanada: Let’s go step by step. First, you mark guidelines. You talk to yourself while doing this, right?

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: My wife sits nearby while I work. I think I’m talking to her, but she doesn’t respond.

Hanada: (laughs) So it’s not really a monologue. You say things like “What should I do?” or “Maybe I’ll do it this way.” From her position, she can’t see what you’re making, so it’s just a kind of imaginary consultation (laughs).

Hanada: When marking guidelines, do you already have a vision, or do you create it as you go?

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: I’d say “as I go.” Or rather, what I roughly decided at first changes as I work.

Hanada: When does it change?

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: “Actually, it doesn’t fit as I thought.”

“Then let’s do it this way, but that’s too much.” “Let’s simplify it and make it neat.” Every time it’s an experiment.

Hanada: That’s the fun of handmade work, the joy of not following a mechanical pattern.

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: If I tried to fit it in too rigidly, it would make my work difficult.

Hanada: What is important when marking guidelines?

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: (pauses) Don’t overmark… At first I was anxious and marked too many points, but then I couldn’t see anything. The line I carve with the tool is the real thing, yet I over-rehearsed with the guidelines and lost track of where I was (laughs). I got misled by my own draft.

Hanada: Like tiring yourself out with rehearsal before the real school play (laughs).

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: Ultimately, as long as the start and end points are set, everything in between will fall into place.

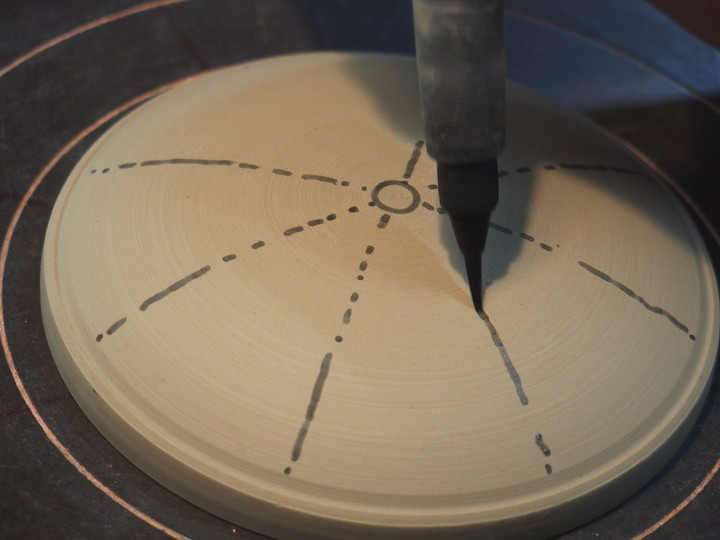

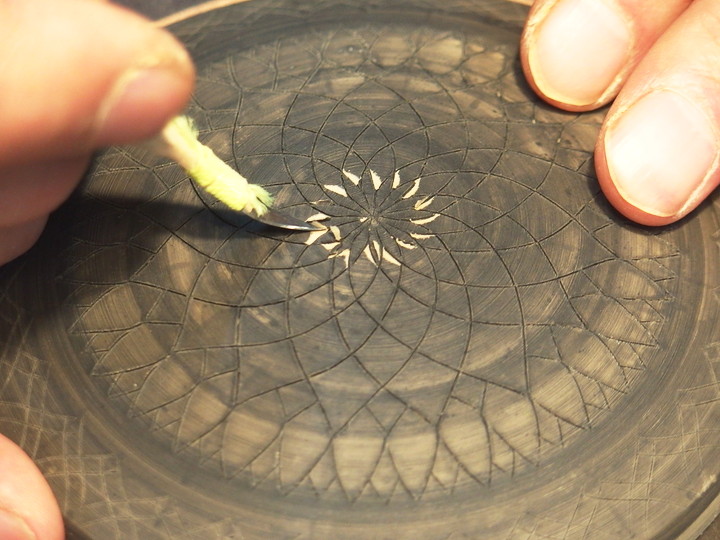

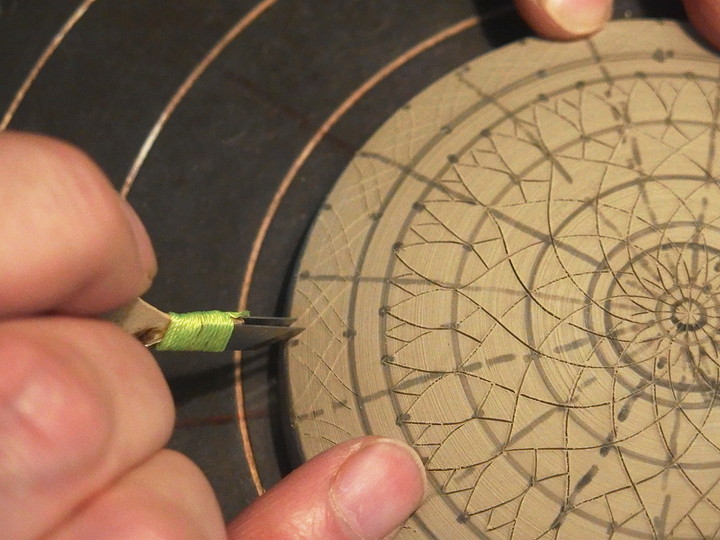

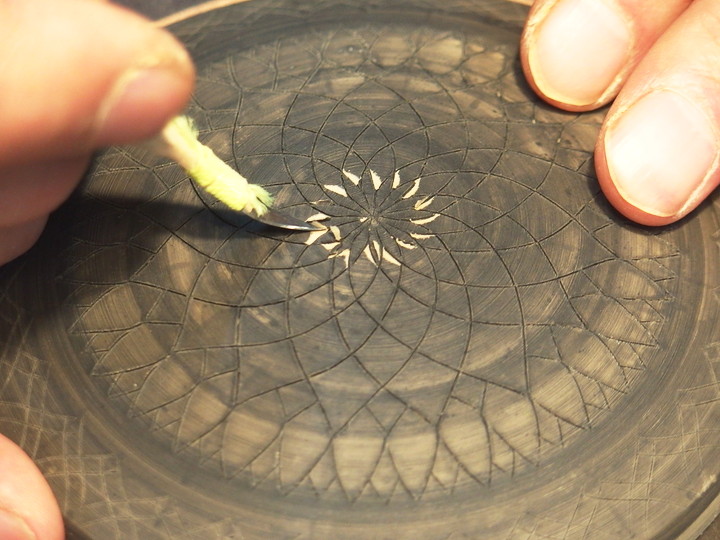

Line Carving

Hanada: Next, you carve the lines.

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: In painting terms, it’s called bone drawing, or line carving.

Hanada: When carving the lines, the freehand feel is nice. You mentioned being careful about depth—does that affect the next step, or is it for appearance?

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: It hardly affects the appearance. But if the blade is too shallow, burrs remain underneath. Too deep, and the cut may split and spread. So it must be just right.

Hanada: Anything else you pay attention to?

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: I try not to let my hand shake while working (laughs).

Hanada: (laughs) Earlier, it wasn’t shaking. Was that at the beginning?

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: I’m not good at holding brushes, so at first my hand shook.

Curves were hard. I was used to straight lines.

Hanada: You said that in Seto, you were only drawing Tokusa patterns. With those, you could draw them even lying down (laughs).

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: Yes. Because they’re straight lines.

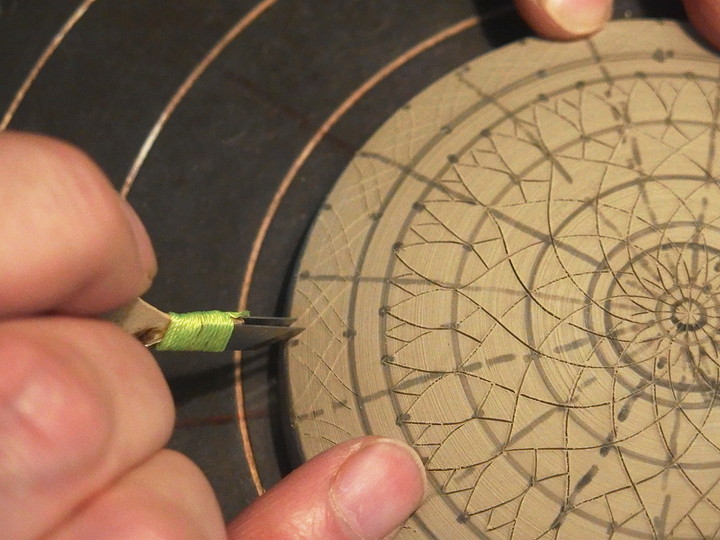

Smooth Scooping Motion

Hanada: And the main…

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: Carving in depth.

Hanada: Does the expression change depending on how you carve?

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: Depth matters. Recently I carve as shallow as possible. Shallow, long, and smooth. If I carve deep immediately, it lacks depth. It becomes simply either “ON” and “OFF.” I carve in a smooth scooping motion.

Do Not Carve Through!

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: And do not carve through (laughs).

Hanada: If you go through, it spills over the next area?

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: Going beyond the line carving would make it sloppy.

It’s important to keep it crisp.

Hanada: Your carving was very rhythmic.

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: Rhythm is important in any task.

Hanada: Do you not pause?

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: Pausing is forbidden. If you stop midway, you lose track (laughs).

Original vs Copy

Hanada: How do you come up with new patterns? By looking at other ceramics, paintings, photos…? Do you get hints that way?

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: Not consciously. If someone told me to copy something, my hands wouldn’t move.

But inspiration comes from everyday life and experiences.

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: The same goes for bands. (He also pursued music in a rock band.)

Hanada: About bands? (laughs)

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: I made originals because I couldn’t copy. Ceramics is the same.

Hanada: A band that only does originals is cool.

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: I just had no choice but to think for myself (laughs).

Hanada: Some people can only copy.

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: People who can copy are admirable. Seeing those who can mimic classics, I’m impressed.

Things I Don’t Want to Tell People

Hanada: Any goals moving forward?

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: Embarrassingly, I don’t want to tell people, but… it’s the Tokyo National Museum. I want to surpass the person who made the Korean celadon carved inkstone screen I saw in an exhibition.

Hanada: Set your goals high.

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: We see the finished work and can set goals. But for the makers, they had no model to follow. They built it from nothing. It’s amazing. But they’re human, too. Regarding carving alone, leaving aside materials and firing, I hope to keep the possibility of surpassing them.

Hanada: They weren’t using special tools at the time, right?

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: Today I can use better tools.

Always on My Mind

Hanada: Finally, what’s the charm of carving?

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: Can I be honest? (laughs)

Hanada: Sure.

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: I keep thinking, “Why did I start this?”

Hanada: You think that sometimes.

Tokuhiro Masubuchi: No, I think that all the time (laughs).

Hanada: Thank you for your fitting final words(laughs).

≪ END ≫

増渕さんは昨年8月以来の展示会です。

前回は、増渕さんに幅広くお話しを伺いました。

今回は、現在の増渕さんの仕事の象徴とも言える「彫る」仕事についてお聞きしています。

増渕さんにとって「彫る」仕事とは。

「彫り」始める

花田: 彫りの仕事を始めたきっかけはなんだったのですか。(以下 花田-)

増渕: きっかけは東京国立博物館の常設です。

工芸品がズラリと並んでいるじゃないですか。

木工、金工、蒔絵なんかの超絶技巧系。

「あー、やってみてー!」って。

-: あそこ、ゆっくり見られますしね。

増渕: 「勝てないな、これは」と感じる反面、迫りたくもなるわけです。

「まあ、やれるところまでやってみるか」と。

じいさんの影響も強いかもしれません。

-: どういった影響ですか。

増渕: 学生の頃に鍛金、彫金を専攻し、晩年は木工などをしていて、彼の作ったものが家にゴロゴロあったんです。

そういう中で、槌目やノミ跡みたいなものの心地よさっていうのは、小さい頃から感じていました。

-: 焼き物という土俵で、そういうものに取り組むことになったわけです。

増渕: そう、自分には焼き物しかできない。

果たして、あれを焼き物で目指す必要があるのかと考えました。

-: 焼き物である理由とは?

増渕: 成形したものに、ノミの跡や、切ったり彫ったりした跡を残して、その上にガラス(釉)を乗せてカタチにするというのは、焼き物にしか出来ないだろうなって。

例えば七宝焼きなんかは食器としては使いづらい素材なので、難しいでしょう。

-: そして「彫る」仕事に邁進していくことになります。

「機械」と「人間の手」

-: 増渕さんの「彫る」仕事は、現在手作りと呼ばれるものの印象、皆が期待するものとは離れた位置にあると思います。

「手作り」っぽくは、ありません。

増渕: そう思います。

-: だからこそ、自分の手でやらなければいけない理由ってあると思います。

「機械でやったらこうはならない」っていう部分はありますか。

増渕: そう願いたいですね(笑)。

人間の手って、いい意味で狂うんです。

アタリ通りにもいかないし、そもそもアタリだってきっちり測ったわけではない。

でも、人の手って、そういう狂った時、勝手にごまかしてくれるんです。

-: ごまかす・・・。

言い換えれば、柔らかく修正してくれるわけですね。

増渕: そもそも、僕なんか47年間ごまかしながら生きていますからね。

ごまかしの人生ですよ・・・(笑)

-: 急にふざけないでください(笑)。

増渕: 一定の触れ幅を保ちながら、合わせるところには合わせていくことが大事だと思います。

点と点をきっちり合わせる作業は機械のほうが得意でしょうけど、複数の点を線にしていくのは今のところは人間に分があるんじゃないかなって思います。

原型を超えることはない

-: 増渕さんは大変な手間をかけてこの仕事をしています。

増渕: 型でやることを考えたこともあります。

でも、型モノだと、原型や型を超えることはないと思っています。

-: エッジが立たないし、ゆるくなる感じですか。

増渕: 原型があって、元型なり使用する型になっていく段階を経ることに、ぼやけていくんですよね。

で、型に粘土を打ち込んでいく工程で、また一つぼやけてしまう。

-: 型モノが悪いということではないと思うのですが、増渕さんが表現したいことのためには、こういう選択肢を取らざるをえない、ということなんでしょうね。

増渕: 型物のソフトフォーカスな感じもいいけど自分は原型です、やっぱ。

-: 増渕さんは原型をずっとやっていることになりますね。

増渕: 工業製品を見ていても、原型が一番格好いいですもの。

プロトタイプとか。

例えば、車のクレイモデルなんて、職人さんが直接削っているんですから。

そこからプレスラインを割り出していくわけじゃないですか。

で、技術や経済との折り合いをつけていく中で、かたちを妥協する部分も出てくる。

僕が彫りの仕事でやっていることって、ずっとプロトタイプですよ。

アタリをつける

-: 工程を追っていきましょう。

まず、アタリをつけます。

増渕さん、アタリをつけるときに、独りで何か喋っていますね。

増渕: 普段、妻がすぐそこに座って作業をしています。

僕は話しかけているつもりですが、返事が来ないってだけの話です。

-: (笑) 独り言ではないわけですね。

「どうしようかな」とか「こうしようかな」とか言っているじゃないですか。

奥様の位置からだと何を作っているか見えないし、話しかけかけられても相談に乗りようがないといった中での問いかけですね(笑)。

-: アタリをつける時、最初からある程度ヴィジョンは持っているのですか?

それともやりながら作り上げていく感じですか。

増渕: 「やりながら」かな。

いや、やりながらというか、はじめに大体決めていたことが、作業していくうちに変わってくるんです。

-: どういう時に変わるんですか。

増渕: 「いざやってみると、案外はまらないな」みたいな。

「じゃあ、こうしよう、でもこれだとくどいな」

「じゃあ、こうはしょって、すっきりさせよう」みたいな感じです。

毎回実験ですよ。

-: それが手作りでやることの面白さであると言うか、機械のようにパターン化させない楽しさですね。

増渕: はめ込んだら、それに合わせようとして自分がやりづらいですから。

-: アタリをつけるときに大事にしていることはなんですか。

増渕: (しばらく考えて) 書きすぎない・・・。

最初の頃は不安で、とにかくたくさん目標点を書いていたのですが、結局それだと何も見えなくなる。

刃物で引く線が本番なのに「アタリをつける」という予行演習をし過ぎて、自分が何番手で走っているのかさっぱり分からなくなってくる(笑)。

自分の下書きに惑わされるんですよ。

-: 本番前に練習で疲れちゃう学芸会みたいですね(笑)。

増渕: 結局のところ、始点と終点が決まっていれば、色々なことがその途中で起きても、収まるものなのです。

骨描き、或いは筋彫り

-: 続いて、筋を入れていきます。

増渕: 絵付けで言えば骨描きです。或いは筋彫り。

-: 筋を彫るときも、即興というか、フリーハンドな感じが良いですね。

深い、浅いといった部分を気にされていたようですが、次の工程に関わってくるのですか。

それとも見た目ですか。

増渕: 見た目には、ほとんど関係ありません。

ただ、刃を浅く差し込むと下にバリが残ってしまうし、深すぎると、筋彫りの切れ目のところが、裂けて広がってきてしまうので、丁度よくする必要があります。

-: 他に気を配っていることはありますか。

増渕: とにかく作業しているときに手がブルブル震えないようにすることで頭いっぱい(笑)。

-: (笑) さっきは、ブルブルしてなかったじゃないですか。

最初の頃ですか。

増渕: 筆を持つのは苦手なので最初はブルブル。

曲線が引けなくて苦労しました。

もともとは直線ばかりでしたから。

-: 瀬戸でも木賊ばかり描いていたっていう話でした。

木賊なら、寝ていても引けるって(笑)。

増渕: うん。引ける。直線だから。

スーッと鋤取るように

-: で、メインの・・・

増渕: 彫り込みですね。

-: 彫り方によって表情は変わってきますか。

増渕: やはり深さです。

最近はできるだけ浅く掘っています。

浅く長くなだらかに彫っていこうと思っていて。

いきなり深く彫り込むと、奥行が出ないんです。

単純な「ON」と「OFF」になっちゃうから。

スーッとすき取るように彫る感じです。

彫りぬかないこと!

増渕: あとは彫りぬかないこと(笑)

-: 抜けちゃうと隣にはみ出るってことですか?

増渕: 筋彫りより向こうに彫ったら、だらしなくなってしまう。

あれがカチッとしていることが重要です。

-: 彫る作業は、特にリズミカルでした。

増渕: どの作業でもリズムは大事です。

-: 中断はしないのですか?

増渕: 中断は禁物です。

途中でやめると、どこまでやったか分からなくなっちゃうから(笑)。

「オリジナル」と「コピー」

-: 新しい文様などはどのように考え出されるのでしょうか。

他の焼き物見たり、絵見たり、写真見たり・・・?そういうことからヒントを得ることもありますか。

増渕: 特に意識してないです。

絵でも、ものでも、何かをお手本に模しとれって言われると、たちどころに手が動かなくなる。

半面、制作の素材は日常の中にあって、普段見たものや経験したことの中からしか出てこないような気もします。

増渕: バンドもそうでした(増渕さんはロックバンドで音楽を志していたこともあります)。

-: バンドの話ですか(笑)。

増渕: 結局、コピーが出来ないからオリジナルを作ったんですよ。

焼き物も一緒。

-: 「オリジナルしかやらない」バンド、格好良いですけどね。

増渕: コピーが出来ないから自分で考えるほかないってだけです(笑)。

-: コピーしか出来ない人だっている。

増渕: 僕からすれば、出来る人は立派ですよ。

古典の模しなどができる人見ると、凄いなあって思います。

あまり人には言いたくないんだけど・・・

-: これから、目指していきたいことはありますか。

増渕: 恥ずかしくて、あまり人には言いたくないんだけど・・・やはりトーハクなんですよ。

なにかの展覧会で見た朝鮮の青磁の透刻の硯屏。

あれを作った人に勝ちたい・・・

-: 目標は高く。

増渕: 僕たちは出来上がった状態を見ているわけで目標とすることができます。

でも、作った彼らにとって最初にお手本は無いわけです。

なにも無いところから作り上げている。

すごいことです。

でも、同じ人間です。

素材や焼き方は別にして、ただ「彫る」作業だけなら、勝てないこともないのかなって希望は持ち続けたいです。

-: 当時、スペシャルな道具を使っているわけでもありませんよね、恐らく。

増渕: 今のほうがいい道具使えます。

いつも思っていること

-: 最後に「彫り」の仕事の魅力とは?

増渕: 正直に言っていいですか(笑)。

-: いいですよ。

増渕: 「なんでこんなこと始めちゃったんだろう」って思っている。

-: たまにそう思うわけですね。

増渕: いや、いつも思っている(笑)。

-: 増渕さんらしい最後の一言、有難うございました。

「彫り」の仕事 増渕篤宥 -Masubuchi Tokuhiro-

溢れ出る情熱と、並外れた集中力。

増渕さんの超絶技巧をご覧下さい。